The GOP’s Anti-Stimulus Manifesto

Conservative writer Amity Shlaes’ take on the Great Depression is fast becoming the most influential book of the decade.

Author:Raven NoirReviewer:Morgan MaverickJul 31, 2020264K Shares6.1M Views

harpercollins.com

For five years, classical liberal columnist and Council on Foreign Relations fellow Amity Shlaes delved deeply into the historyof the Great Depression. She had been an op-ed editor at the Wall Street Journal, a WSJ columnist reuniting Germany, and a columnist for the Financial Times. She wrote two books, on German national identity and on America’s taxpolicy, critiqued from the right. Both sold well, but neither one foreshadowed the success she’d have with her research on the New Deal.

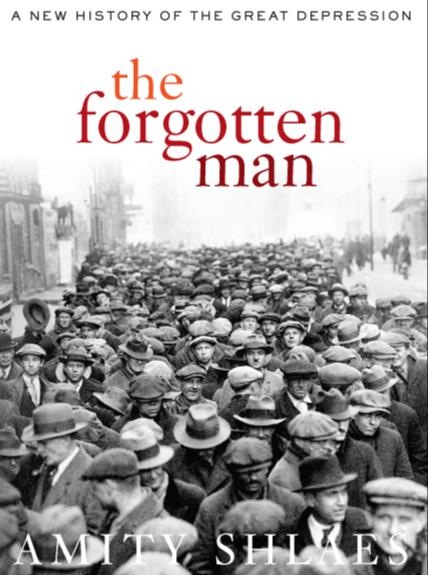

The Forgotten Man: A New Historyof the Great Depression, published in 2007, has become one of the most influential books of the decade. Republicans and conservative activists have read the book, absorbed its lessons, and deployed them in the current debate over how to tackle the greatest economic crisis since the 1930s. Newt Gingrich has read it. So has Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), the ranking Republican on the House BudgetCommittee. And so has Sen. John Ensign (R-Nev.), the headof the Senate Republican Policy Committee; according to his spokesman, the senator has also circulated the book among his colleagues.

“I’m just very fortunate that they’re interested,” said Shlaes on Monday. “This is not an anti-Democrat book, but it is a book that says ‘cast a skeptical eye on stimuli.’”

Image by: Matt Mahurin

There are 200,000 copies of the The Forgotten Man in print, a dramatic success for a work of economic history. Shlaes has written a gripping revisionist historyof the New Deal, told through the interweaving lives of New Dealers and prominent Americans of the era. Republicans, of course, have never been too enamored with Franklin Roosevelt or with the New Deal. But before Shlaes, Republicans and conservatives often sought a sort of compromise with the FDR legacy. In A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900, the conservative Britishhistorian Andrew Roberts writes that “the New Deal worked.” President George W. Bush widely recommended the book and feted Roberts. When the former president pushed for partial Social Security privatization, he presented this as a continuation of FDR’s legacy; conservative commentators such as Brit Hume even suggested that FDR would have supported private accounts.Even if he made mistakes, his style of leadership was worth copying, and some of the outgrowths of the New Deal were worth reforming, not abolishing.

The Forgotten Man’s revisionism does not give so much creditto FDR or his New Dealers. According to Shlaes, whobuilds on decades of New Deal criticism and research into the lives and work of FDR’s brain trust, the programs actually lengthened and aggravated the Depression because of regulation that ate away at American entrepreneurship and profit motive, and because of haphazard implementation that drove businesses and banks to uncertainty and panic. The “forgotten man” of the title is the American whose income and effort were taken, against his will, to pay for the experiments and entitlement programs of the New Deal. The New Dealers, in this telling, were well-meaning and smart people who did a lot of damage and little good, and understanding that is key to understanding why governmentintervention in the economyand big-spending stimulus packages are doomed to fail.

Amity Shlaes (cfr.org)

This argument did not begin with Shlaes, as the author readily admits. Criticisms of the New Deal are as old as the New Deal itself. “Roosevelt drove Republicans mad with rage,” Shlaes said on Monday. “The Republicans who appear in the history of the New Deal were very shrill. It did not become them. So, what can we learn from their mistakes?”

The last decade has seen a sort of boom in New Deal revisionism, beginning with David M. Kennedy’s Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War1929-1945 (1999), which argued that Roosevelt’s programs failed to rescue the economy in the 1930s, and continuing through the work of libertarian Cato Institute scholar Jim Powell, whose FDR’s Folly(2003) built a systematic case that the New Deal actually prolonged the Great Depression. The Forgotten Man has surpassed both books in sales. Powell couldn’t be more pleased.

“I’m kind of hammer and tongs in my approach,” said Powell on Monday. “[Shlaes is] a wonderful, graceful writer who’s, perhaps, more elegant than that. If you’re trying to change opinion on any subject, you need a lot of different people, different voices, and different approaches. That’s true whether you’re trying to abolish slavery or you’re trying to limit the powerof government.”

Among liberals, Shlaes is also the most controversial of the New Deal revisionists. She was roundly criticized on the left for a July 2008 column in which she defendedformer Sen. Phil Gramm’s (R-Tex.) charge that America was in a “mental recession.” New York Timescolumnist Paul Krugman criticizedShlaes’ work and conclusions about the New Deal both before and afterhe won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Economics. But Shlaes has become unescapable on op-ed pages, hungry for contrarian arguments about the stimulus; for example, she has made three appearencesin the WashingtonPost since early December 2008, all of them to argue against repeating the mistakes of FDR. Fred Barnes, the well-sourced editor of the Weekly Standard,reportedthat those columns, like the book, were “widely read” by Republicans.

The Forgotten Man became essential reading among conservatives as soon as it hit the shelves. In June 2007 Gingrich called the book one of two that was “guiding” his thoughts (the other being French President Nicholas Sarkozy’s Testimony). In The Forgotten Man, Gingrich saw a path back to “the Whig-style free-market liberalism” that defined America before the New Deal. “Sarkozy shows us how a courageous leader could translate Shlaes’s call to liberalism into the boldest campaign in our lifetime,” said Gingrich, then flirting with a run for president. Gingrich never ran, but endorsements like that, from a man who many on the right consider an intellectual pioneer, rocketed the book’s popularity on the right.

During the 2008 campaign, Sen. John Kyl (R-Ariz.), the Republican whip in the Senate, bristled at Democratic comparisons between George W. Bush and Herbert Hoover. On September 18, as the economic crisis hit, Kyl argued from the floorof the Senate that “in the excellent history of the Great Depression by Amity Shlaes, The Forgotten Man, we are reminded that Herbert Hoover was an interventionist, a protectionist, and a strong critic of markets. If anything, Hoover-and then Franklin Roosevelt-prolonged the Great Depression by their manic intervention in the free market, which caused a spiral of deflation.”

Since President Obama’s victory, Shlaes’ work, and her columns for Bloomberg News, have provided much of the grist for Republican arguments against a spending-focused economic stimulus package.

In a December 2008 interview with Brian Howey, Rep. Mike Pence (R-Ind.), the third-ranking Republican in the House, fired back at a criticism from Paul Krugman with analysis he’d gleaned from The Forgotten Man. “Shlaes points out… [that] the recession had abated by the middle of the 1930s in the West with the exception of the United States,” said Pence. “She argues that it was the spending and taxing policies of 1932 and 1936 that exacerbated the situation. That’s why I say it’s important for the Congress to act, but one of the lessons of the 1930s is we can’t borrow and spend back to a growing economy.”

Last week, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani cited Shlaes to argue against the idea of spending to get out of a recession. “Basically it points out why the recession of 1929, which was a bad one, became the Great Depression of 11 or 12 years,” Giuliani told Sean Hannity on his Fox Newstalk show. “It became the Great Depression because of unwise government actions first by Hoover and then by Roosevelt. If you think you’re just going to get your way out of this recession by all kinds of social programs, welfare programs, you’re just going to make it much worse.”

Shlaes wants to wave Republicans off from making the kind of rhetorical or ideological compromise with the New Deal that Republicans made, for example, during the 2005 Social Security fight. “This is a timefor choosing,” she said on Monday, “and I’m not the first person to say that or to use that term in saying so. Reagan could afford to like FDR because, at the time, it seemed possible to keep our entitlements if we reformed them. It turns out that we can’t afford entitlements. We have to choose between Reagan and Roosevelt. You can’t just say you like both Reagan and Roosevelt.”

As conservatives make their choices, Shlaes is still plugging away. Her next book will be a revisionist history of the 1960s and the spending and entitlement programs of the Great Society, tentatively titled — after Richard Nixon’s 1969 speechon Vietnam — The Silent Majority.

Raven Noir

Author

Raven Noir is a captivating and enigmatic news reporter who unravels mysteries with a relentless pursuit of truth. Possessing an insatiable curiosity and an astute mind, Raven delves into the depths of complex stories, unearthing secrets that lie beneath the surface. With a masterful grasp of deduction and observation, Raven stands as a beacon of fearless investigation.

In the realm of journalism, Raven is known for his enigmatic presence, drawing people in with an aura of intrigue. Driven by an unwavering passion for unveiling the truth, Raven Noir continues to shed light on the darkest corners of society. Through captivating storytelling and unwavering determination, he challenges conventions and uncovers enigmatic secrets that lie just beyond the surface.

Morgan Maverick

Reviewer

Morgan Maverick is an unorthodox news reporter driven by an insatiable hunger for the truth. Fearless and unconventional, he uncovers hidden narratives that lie beneath the surface, transforming each news piece into a masterpiece of gritty authenticity. With a dedication that goes beyond the boundaries of conventional journalism, Morgan fearlessly explores the fringes of society, giving voice to the marginalized and shedding light on the darkest corners.

His raw and unfiltered reporting style challenges established norms, capturing the essence of humanity in its rawest form. Morgan Maverick stands as a beacon of truth, fearlessly pushing boundaries and inspiring others to question, dig deeper, and recognize the transformative power of journalism.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles